By Hanna Krueger Globe Staff, Updated May 29, 2021, 5:15 p.m.

When Peter Wang landed around midnight at Logan Airport last week for his first business trip since early 2020, his seatmate offered up some advice: Order your Uber now. Wang looked around. The seat-belt light was still on. He thanked the local for her tip but decided to wait until he deplaned to open the ride-hailing app.

An hour and a half later, Wang, a data science executive from Austin, Texas, was still at the airport and so desperate to get to Harvard Square he considered hitchhiking. The Uber and Lyft apps were barren. Public transit had shuttered for the evening. Wang eventually snagged one of the taxis trickling in every five minutes, leaving behind some two dozen other passengers stranded in the fluorescent glow of the vacant taxi stand.

To those who rely on ride-hailing apps to get around Boston, Wang’s story likely comes as no surprise. As the newly vaccinated masses venture out into the world again, they have found readily available Ubers and Lyfts to be a pre-pandemic memory. Local riders and drivers alike agree that current demand far outpaces supply.

Ride-hailing companies are grappling with a nationwide shortage of drivers. The number of US-based drivers logging into Uber during the first three months of 2021 was down 37.5 percent year over year, according to data from Apptopia, a Boston-based market intelligence service. Lyft saw a 42.3 percent drop over the same period.

Nowhere is the problem more acute than in Boston. The average wait time for an Uber in Boston this spring is 40 percent longer than in Philadelphia and 147 percent longer than in New York City, according to a company spokesman. Lyft did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

“Extreme sports — getting an Uber in Boston,” wrote one Twitter user in mid-May.

Perhaps the most obvious culprit for the shortage is a 2016 Massachusetts law that bans surge pricing during states of emergency. Without the incentive of that added revenue, drivers see little point in hitting the streets during rush hour or thunderstorms, and on weekend nights.

Lawmakers instituted the ban to protect MBTA riders from outrageous Uber and Lyft fares after the notorious February snowstorm of 2015 shut down public transit. But drivers argue that there is a major difference between a blizzard — a transient hardship — and a 16-month pandemic.

“The demand has completely returned to a pre-COVID level and the drivers just aren’t there,” said Jake Irmitir, who began working as an Uber driver again in August when his unemployment assistance ended. “Being a driver right now means you’re making like a third of what you used to make because of no surge pricing.”

The Baker administration has introduced legislation to modify the blanket ban on surge pricing in an effort to “increase the supply of drivers, which reduces wait times and ensures reliable transportation options.” The third and most recent bill was filed in April, but has not yet been taken up by the Legislature. Massachusetts is one of just two states that have imposed such a ban.

Still, even the ride-hailing companies recognize the reintroduction of surge pricing alone won’t solve the driver shortage plaguing cities across the country. Much of their driver base filed for unemployment when the country shut down last spring. And in a dilemma that mirrors that of the restaurant industry, many drivers realized that their unemployment checks eclipsed what they often earned driving, especially after deducting car expenses and gas prices, which are currently at a seven-year high.

Others switched to driving for food delivery services, according to Beth Griffith, executive director of the Boston Independent Drivers Guild. Gone were the lengthy rides with drunk, reckless customers and the out-of-pocket tolls necessary for an airport pickup. Those without child care could even take their kids along for deliveries when needed.

COVID-19 concerns have also held some back. Felipe Martinez, a full-time driver who has diabetes and has two young children, stopped driving last March to protect himself and care for his kids. Today, as Massachusetts opens up, he is one of several area drivers torn between a fear of the vaccine and a fear of the virus.

“Rideshares are mostly a Black, brown, and immigrant workforce, and there is this mistrust of the government that is keeping a lot of drivers off the roads because they don’t want to get the vaccine,” said Griffith.

Despite Massachusetts’ reputation as a vaccination powerhouse, the state’s Latino and Black populations still remain under-vaccinated. Roughly 60 percent of Uber drivers identify as non-white, according to several surveys conducted across the nation.

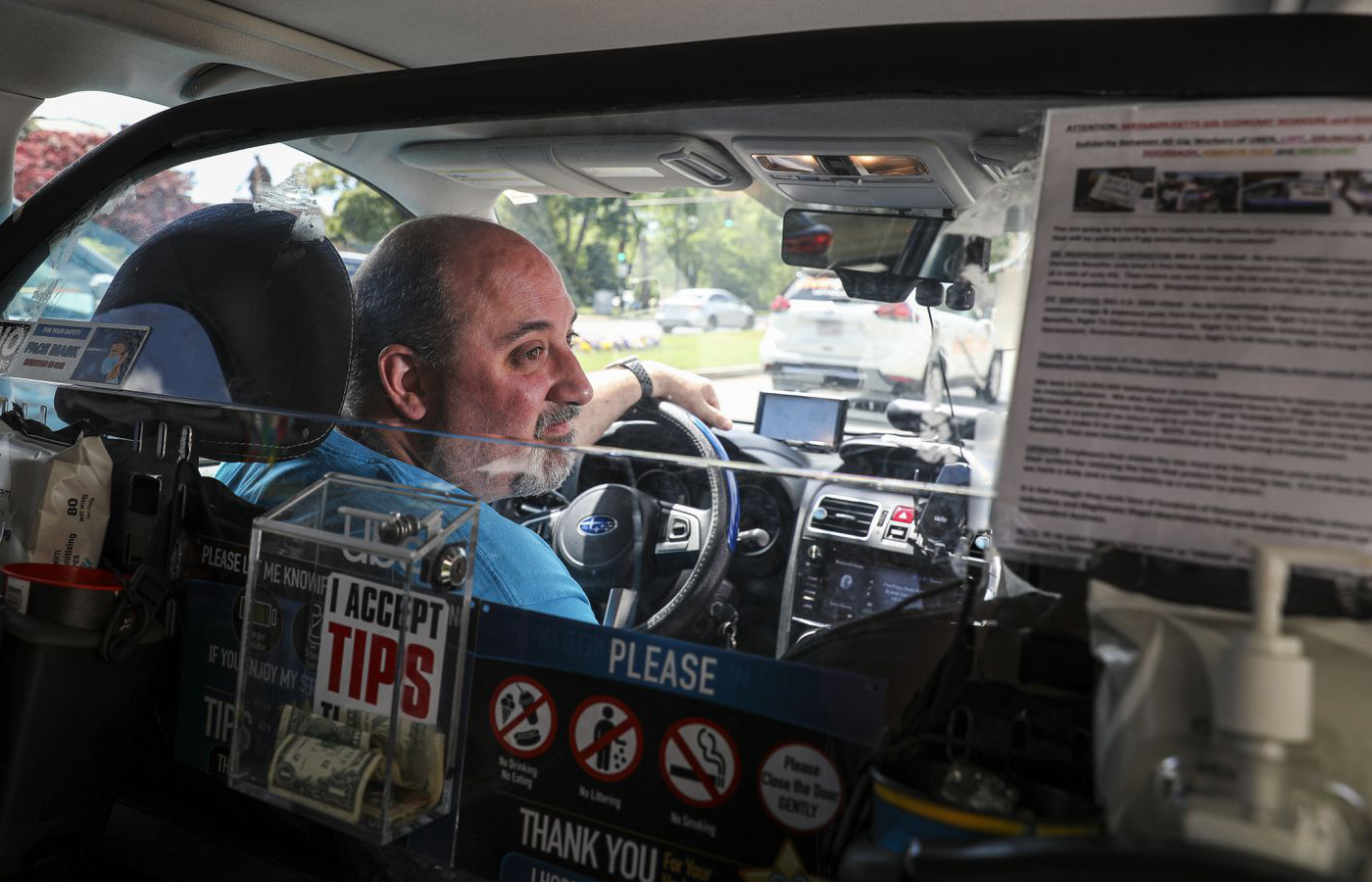

Those drivers who have returned to the roads told the Globe that they’ve encountered the same festering labor issues that existed before the pandemic. Drivers said that, at best, one out of 10 riders tips and traffic has roared closer to its hellish pre-pandemic norm. Uber recently unveiled a $250 million stimulus package aimed at welcoming back existing drivers and recruiting new ones with small bonuses.

“As more people are getting vaccinated and moving around, riders in Massachusetts are using the Uber app more. That’s why we have temporarily boosted earnings for Uber drivers to encourage them to drive with us,” said Uber spokesperson Alix Anfang in a statement.

But drivers emphasized to the Globe that the incentives offered through the initiative are merely temporary and not retroactive, meaning the few who have been anchoring the service over the past few months will not benefit.

“I drove through the winter and they decreased my incentives while offering former drivers practically free money! That’s my reward for providing service through one of the riskiest times of the year,” wrote one Boston driver, who asked to remain anonymous for this story for fear of reprisals by Uber and Lyft.

This feeling of expendability has long been an issue for ride-hailing companies that have fought tooth and nail against making full-time drivers employees, while still relying on them for a disproportionate amount of revenue. The companies are tight-lipped about how many drivers work over 32 hours a week, but a July 2020 study by Seattle researchers revealed that a third drive full time in the city, accounting for 55 percent of trips.

“We just get hit around like the kid on the playground getting beat up by a bully,” said Stephen Levine of Lynn, who started driving for Uber full time in 2015 at a base rate of $1.24 per mile. That same rate has since decreased to 66 cents.

It may not happen overnight, but local drivers envision the balance tipping back in the rider’s favor in the coming months as new drivers enticed by temporary incentives join and the state of emergency ends on June 15.

Historically, the summer months are the worst for ride-hailing drivers who rely on Boston’s college students to sustain them. The mass exodus of these students creates a saturation of drivers, said Griffith.

“Some go down to the Cape where there is less competition and essentially live out of their car and use a gym membership to shower in order to earn a living wage,” she said.

And while the phenomenon of hitchhiking CEOs may disappear, the fraught relationship between ride-hailing companies, their drivers and the state will not, particularly with more attention paid to labor practices among tech behemoths. Baker may double down on his efforts to increase five-fold the state’s surcharge on ride-hailing companies, using the revenue to fund public transit. Lyft and Uber argue that it is not their responsibility to plug state budget holes and the surcharge would lead to an increase in rider fares without a pay increase for drivers.

“The state considered us essential employees in the pandemic, and the city buckling without us now shows just how essential we are,” said Levine. “But it’s a very hard situation we are in with little light at the end of the tunnel. Until we are protected by law, we can’t really celebrate anything.”

Hanna Krueger can be reached at hanna.krueger@globe.com. Follow her on Twitter @hannaskrueger.